How to Build a Chromatic Scale

November 28, 2022 by Taras (Terry) Babyuk

Introduction

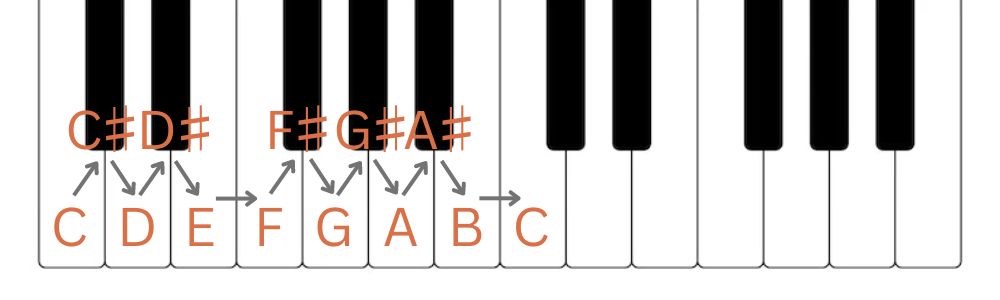

The chromatic scale is a scale made up of 12 different notes separated by half-steps (semitones). The 13th note is a repetition of the 1st note an octave apart. On the piano keyboard, if you start on any key and play every note (white and black) in order one octave up or down, you will get a chromatic scale.

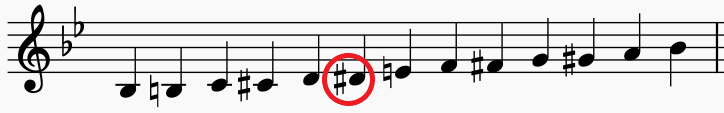

In music theory, we often write the chromatic scale in both ascending and descending form, separated by a bar line. The bar line makes it easier to write the descending part of the scale by cancelling out all preceding accidentals (see example below).

Unlike major and minor scales, there is more than one correct way to write chromatic scales. At the end of the day, our main guiding principle should always be to make it as readable as possible for the musician, who will, after all, be playing the notes! With this thought in mind, let's dive in and see how we can build the chromatic scale!

Unlike diatonic scales like major and minor, chromatic scales are not based on any key. So for a chromatic scale from the note C, we would just call it "Chromatic scale starting on C", as opposed to "C chromatic scale". This is an important distinction to keep in mind.

Rules for Notating Chromatic Scales

When writing/notating a chromatic scale, such as on a music theory exam or in a musical composition, there are some basic rules we need to keep in mind. Here they are:

- Do not change the starting note enharmonically

Whatever note your chromatic scale starts on must always be written the same way. So if you start on "G♯" for example, do not call it "A♭" later in the scale. - Do not use the same letter name more than twice in a row.

For example, we can not write "F♭", "F♮" and "F♯" when writing a chromatic scale, as this would be using the same letter name ("F") three times. - For chromatic scales without a key signature, try to use sharps when ascending and flats when descending.

This is because for musicians, sharps are easier to read when going up and flats when going down. - For chromatic scales with a key signature (such as in a musical score), choose accidentals based on the key signature.

This means that if the key signature is made up mostly of flats, stick with flats when writing your scale (even the ascending part). The same goes for sharps.

Writing Chromatic Scales with and without Key Signatures

Chromatic scales can be written with or without a key signature. Scales without a key signature are common in music theory exercises or in technical exercises for your particular instrument. In sheet music and musical scores, however, you will often find chromatic passages in a piece of music that is in a specific key. In such cases, the composer has to incorporate a chromatic scale into the key signature. Below, we will see examples of how to write chromatic scales in both situations.

1. Writing a Chromatic Scale without a Key Signature

If our starting note is either a natural or a sharp note, use sharps for the ascending and flats for the descending part of the scale, as per Rule #3 above. Here are some examples:

When the starting note is a flat note, we might need to use some flats and natural signs when going up in order not to break Rule #2 above, but we should switch to sharps as soon as possible as per Rule #3. Here is an example:

Notice that in the scale above, we switched to sharps as soon as we could, after the note "F". Before that, we had no choice but to use flats and naturals.

2. Writing a Chromatic Scale with a Key Signature

As mentioned earlier, there is more than one way to write a chromatic scale, and this also applies to chromatic scales with key signatures. The method I will be demonstrating here is one recommended by the ABRSM (Associated Board of the Royal Schools of Music), which I quite like. This method requires us to add one more rule to the four rules we saw earlier. And that rule is:

5. The 1st, 4th and 5th degrees of the scale should be represented unaltered.

In other words, the notes representing the primary triads of our key should be written in the form in which they naturally occur in that particular key.

Let's see how this works in practice by writing a chromatic scale occuring in a key of "B♭ major".

We know that the key signature of "B♭ Major" is "B♭" and "E♭" and we also know that the 4th and 5th degrees of this scale will be "E♭" and "F", respectively. Let's keep these facts in mind as we write out our scale.

Note that we did not use sharps at all in the ascending part, as recommended by Rule #3. Instead, we stuck to flats as per Rule #4, to keep things consistent throughout our scale. If we had used sharps, this is how our ascending part would look.

While this version might also be considered fine, it's not preferred. Not only are we not being consistent with our accidentals, but we're also not following the rule of having our subdominant note unaltered here. Instead of having an "E♭" for the subdominant, we are writing it as "D♯" and therefore violating our rule.

Here are a few more correct examples, for variety.

Example of a Chromatic Scale in Music

See a real-world example of the use of chromatic scales in the famous composition by Rimsky-Korsakov called "Flight of the Bumblebee".

Conclusion

Chromatic scales add color and interest to musical compositions and you are bound to come across them may many times in your musical journey. Hopefully you now have a much more solid understanding of how these scales work from a theoretical perspective as well as the knowledge of how to correctly write then in music notation. Good luck!

Just fill out our quick trial lesson form and wait to hear from us within 1-2 business days. If you like your trial lesson, you can sign up for regular lessons with us! Our lessons are available online (Zoom or Skype) as well as in-person if you live close to our location. Start learning your favorite instrument with one of our amazing teachers today!